Shippers over the past year have attempted to institute structural changes in their operations to avoid being stung again like they were in 2018, when a sudden spike in freight — and an already constrained trucking capacity — undercut their ability to move loads and busted transportation budgets.

“We’ve been focusing on reducing inefficiencies,” says Robert Savage, vice president of logistics for Del Monte Produce, a major produce shipper. One area of focus for Del Monte has been to reduce detention times at its facilities for its carriers, he said. The company overhauled its contracts to start paying carriers detention fees after two hours instead of three hours, to try to press its shipping locations for more efficient loading and unloading. The policy so far has paid off, with detention times at its facilities being cut from three hours last year on average to an hour and 20 minutes this year. “Detention is a big problem for us,” he said, “especially at the ports.”

From left: Chris Pickett, Coyote Logistics; Robert Savage, Del Monte Produce; Bill Matheson, Schneider National; Chris Kravas, Bulkmatic Transport; Avery Vise, FTR.

From left: Chris Pickett, Coyote Logistics; Robert Savage, Del Monte Produce; Bill Matheson, Schneider National; Chris Kravas, Bulkmatic Transport; Avery Vise, FTR.Savage spoke on a panel at the 2019 FTR Transportation Conference in Indianapolis on Wednesday. Joining him were Bill Matheson, senior vice president and chief commercial officer at Schneider National; Chris Pickett, chief strategy officer at Coyote Logistics; and Chris Kravas, president of Bulkmatic Transport. Avery Vise, vice president of trucking for FTR, moderated the panel discussion.

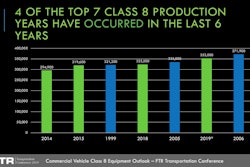

2018 presented “an extraordinary set of conditions,” says Matheson, pointing to major weather events in late 2017, the hard adoption deadline of the U.S. DOT’s electronic logging device mandate and maxed-out trucking capacity. “All of those converged and caused the industry to struggle” to keep up with freight demand, he said.

Though many carriers celebrated those conditions and the fat per-mile rates they bore, shippers in turn “had a tough year,” Matheson said. That’s not something Schneider really celebrated, he said, given that its shipper customers had a hard time moving their freight. “I’ve been in this game too long. We’re in a cyclical game. We like to provide value to our customers.”

When logistics managers at shippers reviewed their performance for the year, they likely had to tell their bosses they didn’t have the capacity coverage necessary to move their freight, said Matheson, and, perhaps worse, likely spent well above their transportation budget.

“Shippers are not going to sit back and allow that condition” to continue, Matheson said, or to let it strike again. The market has since regained balance, due in part to more supply entering the truck market. Some shippers are leveraging market conditions and funneling freight the spot market to take advantage of cheaper rates. But “that’s not durable,” says Matheson.

Instead, many shippers are using new tools to adapt “in the midst of a sea change,” he says, such as those that increase visibility of available capacity. This allows them to “get better coverage and costs — fast,” he says. Such visibility provides shippers with temporary coverage when needed as well as longer-term commitments to rates and capacity from carriers that allows them to shift more nimbly amid market cycles.

“It’s an emerging trend,” said Matheson, that should “continue well into the future.”

Data from ELDs is also helping carriers and shippers better understand where their inefficiencies lie and help alleviate hang-ups, he said.