Donald Broughton, managing director of Broughton Capital and a longtime favorite of business news television, predicted at Commercial Carrier Journal's Solutions Summit in Arizona last week that the U.S. economy had only started chipping away at economic boom in store for the coming quarters.

Broughton, who delivered a comprehensive macro level analysis of the U.S. and global economies, essentially said that supply side problems like semiconductor shortages would soon end, supply chains would shorten and onshore, and that the trucking industry would remain in boom times into the foreseeable future. Broughton came armed with detailed slides and analysis of the economy to conclude that the U.S. would remain the world's leading economy by a long shot, that China would fall behind and that a shift in consumption toward high-value, low density goods, like iPhones, would transform the freight industry entirely.

"At times I am very, very bearish," said Broughton, "but I have never been more bullish about the U.S. economy than I am right now."

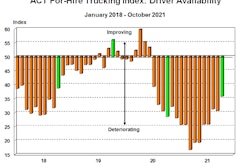

While Broughton acknowledged challenges for the trucking industry, like a lack of new tractors, soaring used truck prices and recurring recruitment and retention challenges, his analysis suggested these were merely symptoms of the early stages of an economy in a historic boom.

"Pick up any newspaper and look at any headline," said Broughton. "Every single one is indeed growing pains if you look at them and devolve them. In 20 or 30 or 40 years, historians will call this period the great post-COVID boom, and we’re only in the first inning. The first pitch has just been thrown out."

The roaring '20s all over again?

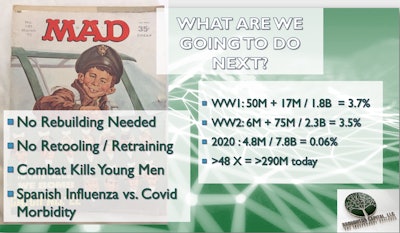

Broughton stressed using an anthropological lens to look at the country's current economic situation and found the most pertinent historical analogies for today's age in the post-WWI/Spanish Flu pandemic and the post-WWII periods. But even with an ongoing global pandemic comparable to a world war going on, he found cause for bullish propositions.

"History doesn’t repeat itself, but it sure does rhyme," said Broughton. "What I do find value in is to look at what is different than other times. Cycles repeat, but with nuances. This is a part of a cycle that we have survived. We feel like we survived something together."

This, he said, would be cause for celebration. Broughton said it was no coincidence that an economic boom in the 1920s followed the Spanish Flu, and that the economic boom of the '50s and '60s followed WWII. But, in looking at "what is different" between the pandemic and great wars past, Broughton found only silver linings.

While acknowledging the immense human and personal costs of the COVID pandemic, Broughton found morbidity rates exponentially lower than wars and pandemics past, and the economic losses more akin to shifting gears than wheels falling off.

"The Spanish Flu killed 50 million people when the global population was 1.8 billion, and morbidity was concentrated in those 20 to 30 years old," said Broughton. WWII's 75 million deaths similarly concentrated around the young.

"These events killed young people that had decades of economic productivity and consumption ahead of them," said Broughton. Similarly, after the great wars, entire countries needed rebuilding and industries retooling. Broughton compared that to the Dow Jones Industrial Average tanking 6,000 points in March and crawling back to new all time highs within a year. That American businesses shifted to online operations "within months" bodes well for the economy, as the future of commerce will take place online, and the U.S. still holds the advantages in making tech hardware and software.

With only 1.6% of COVID deaths occurring in those 41 and younger, and the retooling and retraining happening during the pandemic, not after, Broughton's predictions for an economic boom rest on significant demographic trends unique to our time.

The future of supply chains

Broughton chided businesses in 2021 for blaming "supply chain issues" and turning it into a "widely used" excuse that remains poorly understood. Nevertheless, Broughton predicted shortages from semiconductors to lumber to fuel would be resolved "within the year" thanks to the productivity-enabling technology in place across the supply chain.

"Simply stated, the professionals who manage today's modern supply chain have the tools, the intellect and the resources to solve all of the current problems," Broughton said.

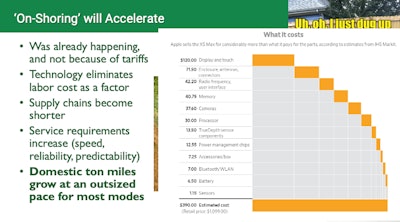

Unlike other economists who predict supply chains will normalize after pandemic-induced demand dies down, Broughton expects demand to continue to soar and supply chains to remake themselves through radical onshoring.

"Supply chains will become shorter. You can't manage a supply chain that's too long, and they can't get any longer," said Broughton. Broughton predicted auto manufacturing supply chains would shorten up, and in doing so, increase the ton miles up for grabs in the U.S. freight market.

"When you onshore you get a multiplication of domestic ton miles," he said. "That's part of this explosion of freight and why demand is so strong."

Broughton compared moving a car from a port to a dealership with a single car hauler trip versus making a car in the U.S., which would require moving metallurgical coal and steel from plants to the manufacturer and again to the dealership. For Broughton, this all adds up to more demand for trucking.

Furthermore, he said the U.S. can now afford to onshore manufacturing again because the cost of labor has dropped so dramatically. After decades of companies chasing lower labor costs to Mexico, then China, then Vietnam, Broughton said auto manufacturing is done by robots now, and robot's don't earn wages.

Outside of manufacturing, Broughton cited the fracking revolution that catapulted the U.S. to the forefront of international oil and gas exporters. According to Broughton, fracking will increase domestic ton miles while securing the U.S.'s place as an energy exporter, and riding the coattails of that boom would be an explosion in agriculture, housing, chemicals and consumer spending.

Technology to transform what freight is and how it's moved

Not only will technology enable a streamlined supply chain and more onshoring, technology is quite simply what people want to buy, according to Broughton.

"If you look at value density, tech goods themselves become higher in value and lower in density. IBM's supercomputer becomes a laptop which becomes an iPhone," over time, he said. "All the new goods are high-value, low-density. We're not inventing new kinds of sand. If I ship you materials to build a building, that's a lifetime ship. But, if I ship you an iPhone, in three years I'll ship you a new one."

E-commerce's transformation of the freight industry will continue, Broughton said, noting that large shipping operations like Amazon and Walmart have significantly different challenges than the old model of freight moving.

"Not 90%, not 98% of loads, but 100% are cubing out before they weigh out," he said of e-commerce shippers. "Ton miles are going to explode in these e-commerce lanes."

What regulations to expect?

During the questions segment, the CCJ Solutions Summit audience asked Broughton what he predicted in the regulatory environment with regard to trucking. His answer: Not much.

"The ability of government to regulate business has diminished and continues to diminish," said Broughton, who cited the case of courts telling FedEx that drivers with company uniforms and decals on the trucks counted as employees, only for FedEx to slightly lower driver pay and add bonuses for drivers who wear the uniforms and use the decals. Broughton predicted that rules like AB 5 would meet other inventive private sector solutions to soon render them irrelevant.

Similarly, on the climate change front and recent swing towards ESG investing, Broughton again saw this as an issue for the market to work out, and that the market would continue to purchase the cheapest kilowatt hours it could.

"Economics overtake social concerns. That’s not my opinion that’s longterm historical record," Broughton concluded.